As India observes Martyr’s Day on 30 January 2026, the nation pauses to remember the man who led a colonial empire to its knees with nothing but a staff, a shawl, and an indomitable will. While history books often focus on his political triumphs or his strategic fasts, there is a profound, quieter lesson found in the very last thing Mahatma Gandhi did before he stepped onto the prayer ground at Birla House in 1948: he ate. At approximately 4:30 in the afternoon, while engaged in a deep conversation with Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel regarding the future of the newly independent nation, Gandhi consumed his final meal. In the modern era of 2026, where food is often a matter of indulgence, fast-paced consumption, or social media aesthetics, the specifics of that meal offer a stark and necessary reflection on the principles of Satyagraha, Ahimsa, and self-discipline.

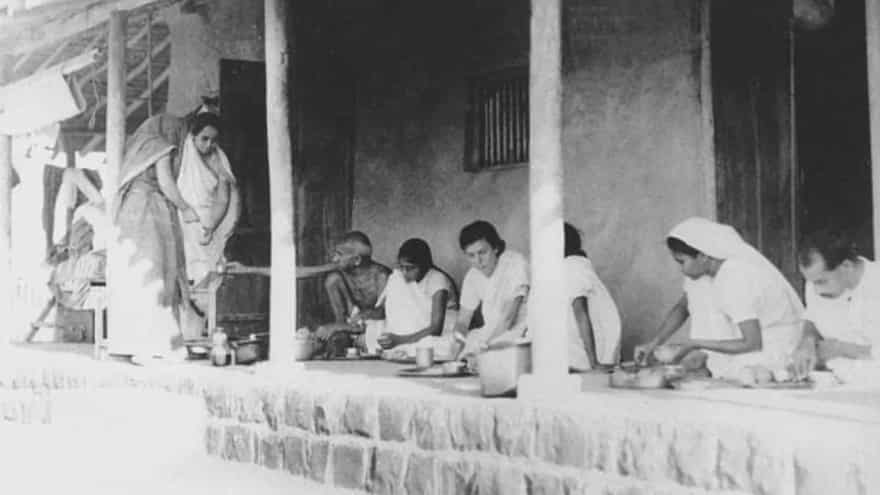

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The Final Menu: A Study In Simplicity

Gandhi’s last meal was not a feast prepared for a leader of millions. It was a humble collection of items that mirrored his lifelong experimentation with dietetics. The tray brought to him by his grand-niece, Abha, contained twelve ounces of goat’s milk, a bowl of cooked and raw vegetables, four tomatoes, and four oranges. To finish, he drank a decoction of ginger, sour lemons, and strained butter, supplemented with the juice of aloe.

Image courtesy: Freepik

This was not a random assortment of food. Each element was a result of decades of personal trial and error. Gandhi viewed the human body as a temple of God, a vessel for service that required precise, clean fuel. The goat’s milk was a compromise he had reached years earlier after a severe illness, having vowed never to touch cow’s milk due to the cruel practices sometimes involved in its extraction. The tomatoes and oranges were sources of vital nutrients, chosen for their freshness and local availability. Even in his final hour, his plate was a manifestation of Swadeshi: the use of local, seasonal resources to sustain the self.

Asvada: The Control Of Palate

One of the eleven vows Gandhi prescribed for his ashram was Asvada, or the control of the palate. He believed that most people eat for pleasure rather than necessity, which leads to a loss of self-control. For Gandhi, the conquest of the tongue was the first step toward the conquest of the self. By eating plain, often unseasoned vegetables and raw fruits, he was training his mind to remain detached from sensory cravings.

Image courtesy: Freepik

In contemporary India, where lifestyle diseases like diabetes and hypertension are on the rise, this Gandhian principle feels more relevant than ever. His last meal reminds us that food should be treated as medicine. He often remarked that one should eat only enough to keep the body going, and not a morsel more. On that fateful January afternoon, his disciplined intake reflected a man who was entirely in charge of his physical urges, ensuring that his mind remained clear for the heavy political and spiritual duties he carried.

Aparigraha: The Art Of Non-Possession

Another pillar of Gandhian philosophy present on that small wooden tray was Aparigraha, or non-possession. Gandhi sought to live with the bare minimum, believing that to possess more than one needs is a form of theft from those who have nothing. His meal reflected this lack of excess. There were no elaborate gravies, no refined sugars, and no processed grains.

In 2026, as the world grapples with the environmental consequences of overconsumption and food waste, the Mahatma’s last meal serves as a blueprint for sustainability. He advocated for a diet that was low in its ecological footprint long before the term became fashionable. By choosing raw vegetables and fruits, he minimised the need for fuel and elaborate preparation, showing that a life of great impact does not require a life of great consumption.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Ahimsa And The Ethics Of The Plate

While most recognise Ahimsa as the refusal to use physical violence against others, Gandhi extended this principle to the way we treat all living beings and our own bodies. His vegetarianism was not merely a cultural habit but a conscious choice based on the sanctity of life. He felt that a person’s diet should reflect their commitment to peace.

Image courtesy: Adobe Stock

His last meal was entirely free from the violence of the slaughterhouse, but it also reflected what he called dietetic ahimsa. This involved eating foods that caused the least amount of harm to the plant and the soil. He was particularly fond of uncooked greens because he believed that cooking often destroyed the life force of the food. On 30 January 1948, his bowl of raw and boiled vegetables was his final act of non-violence: a gentle interaction with the earth that had sustained him for seventy-eight years.

The Body As A Tool For Service

Gandhi did not pursue health for the sake of longevity alone. He wanted a strong body so that he could be a more effective servant of the people. His rigorous diet was a means to an end: the stamina to walk through the villages of Noakhali, the energy to negotiate with world leaders, and the clarity to draft the constitution for a free India.

His grandson, Gopalkrishna Gandhi, once noted that on the day he died, the Mahatma was five feet five inches tall and weighed only one hundred and nine pounds. Yet, his energy levels were legendary. This vitality came from the deliberate nature of his nutrition. He treated his digestive system with the same respect and order that he applied to the Indian National Congress. His last meal was eaten at a precise time, following a precise routine, because he believed that discipline in small things led to discipline in great things.