Towards the end of the last century (I think it was 1999), Kanwal Grover asked to see me. I knew Mr Grover because I had been at school with his son Kapil from the age of eight (first in Bombay and then in Ajmer) and I knew that having made a fortune in international business, he was now focussing on a personal not-for-profit (well, not yet, anyway) passion: wine.

Mr Grover was convinced that it was possible to make good wine in India. The reason most of the existing Indian wines (we don’t even remember them today; they had names like Golconda Ruby and Bosca) were so revolting was because nobody had tried to make anything of quality.

His passion project was a winery just outside of Bangalore and he called me because, by some coincidence, I was judging a Chef’s Competition in Bangalore. Mr Grover had a request. His winery already made many generic wines. But now, it had produced a red wine he was really proud of. He called it La Reserve and wanted us to serve it at the gala dinner that would announce the results of the competition.

I was happy to help a friend’s father but sceptical that I could persuade the organisers to serve an Indian wine. Fortunately, once they tried La Reserve, they were convinced that it was the finest wine that had been made in India till that time and we served it to universal approval.

Mr Grover had developed a love of good wine during his travels abroad (mainly in France, I suspect) and the vineyard was the sort of indulgence that rich men allow themselves towards the end of their careers. He procured some investment from (if I remember correctly) a French champagne house and hired a French wine-maker.

Eventually, the Grovers turned to Michel Rolland, the French wine consultant who is known as the Flying Winemaker because he advises wineries in so many different countries. The inspiration for the vineyard may have been French but I began to suspect that the style they were aiming for in their wines was more Australian (which probably made sense given the temperature in the Bangalore region).

It’s been nearly two decades since I tried that first bottle of Grover La Reserve and since then, the wine scene has exploded. Mr Grover sadly, has passed on and though Kapil and the rest of his family are still very involved, the company has found new investors and morphed into a larger enterprise and is much more than a millionaire’s labour of love.

But at least the Grovers are still around. Indage, a contemporary, which made the first Indian sparkling wine, lost its first mover advantage and then closed down. Sula became India’s top wine brand because its founder Rajeev Samant understood the Indian market better than anyone else.

And new wineries keep opening (and closing) in Maharashtra’s Nasik region. Many of them, I am sure, are very good though sadly, I have not been fortunate enough to drink any wine that I have really enjoyed from the newer Nasik wineries.

The highest regarded producer of Indian wine now is probably Fratelli, a collaboration between a family of Italian wine lovers, Delhi’s Sekhri brothers, and a well connected family in the Akluj region of Maharashtra where the winery is located.

I like the Fratelli Sette (a red wine that is now made in a Super Tuscan-style) and I wondered, when I tried my first bottle of Sette, if the future of Indian wine-making will eventually consist of collaborations with global winemakers and foreign companies.

I didn’t have to wait long for an answer. Moet Hennessy, the French giant that makes Moet et Chandon champagne launched a sparkling wine called Chandon a few years ago and virtually took over that market segment. Chandon sparkles but it does not taste like Champagne (it is made from a different grape) and Moet-Hennessy have priced it much lower so as to not cannibalise the demand for the pricier Moet et Chandon. But the success of Chandon has taken a huge bite out of the market for Prosecco, a lightweight, cheaper Italian sparkling wine.

The continued triumphs of Chandon (they keep launching new packaging and new variants) led me to try and guess which of the global big boys would hit India next.

The answer, to my surprise, is yet another collaboration between the Sekhris of Fratelli and a global producer. Their latest range (one red, one white and one sparkling) is called J’Noon and is made in partnership with Jean-Charles Boisset.

Boisset is an oddity in the global wine world. In some ways, he is to French wine what Vikas Khanna is to Indian food. A charismatic, flamboyant figure, he makes good quality wine in Burgundy but also has vast American interests where his companies make wines that are very different from the ones they bottle in Burgundy. He is married to a member of the Gallo family (renowned as one of the best known mass wine brands across America) and among the unusual things Jean-Charles and wife have done is to make a wine that blends wines from California and France together.

For a classic Burgundy wine-maker, this is heresy. (Unlike Bordeaux where the wine guys are more international and better travelled, the owners of Burgundy’s vineyards tend to be deeply traditional, low-profile, conservative figures). But Jean-Charles or JCB, as nearly everyone calls him (easier to pronounce in the global market, I imagine) cannot be easily dismissed as a mere showman because he makes solid, good quality, highly regarded wines in both France and America.

JCB and the Sekhris believe that the Indian market is ready to pay for a top class domestic wine. In real terms, this means that they are pricing their wines at the same level as imported wines.

So far at least, one of the attractions of Indian wine has been that it is cheaper than the foreign competition. For instance, I doubt if Moet Hennessy would sell much Chandon if they priced it at the same level as Moet et Chandon. JCB and the Sekhris want to break that orthodoxy and sell their wines on the basis of quality and not on cheapness of price.

Further, JCB believes that the three wines will find a global market. He has glamorous launches planned for J’Noon wines in Napa Valley and Paris (and, very bravely, in Burgundy too if all goes well!).

It has all been well-thought-out. The sparkling wine, for example is made with Chardonnay, a Champagne grape (the wine is a Blanc de Blancs) and not Chenin Blanc which is usually the preferred grape for sparkling wine in India. The white wine breaks with orthodoxy to blend sauvignon blanc and chardonnay, two grapes that are rarely mixed together in France. I liked the silky red wine which was so cleverly made that it would be hard to say, if you tasted it blind, where it came from or even what the wine-making style was.

Will it work?

So far, JCB and the Sekhris are playing it safe. Production is relatively small and I imagine they will only increase the volumes once market response has been tested.

But given JCB’s record of pulling off marketing coups and the strength of his distribution network all over the Western world, it seems reasonable to say that he wouldn’t put his name to a venture like this unless he was confident of its market potential.

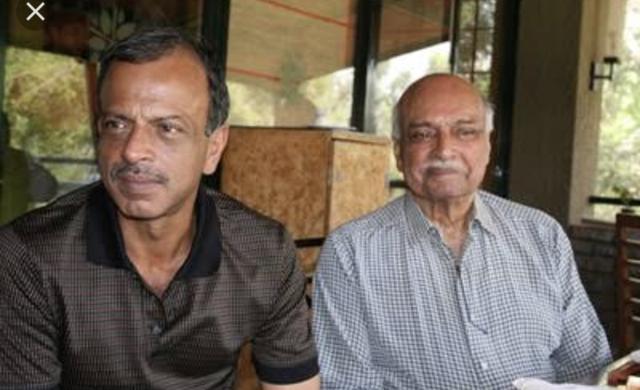

I had dinner with JCB and the Sekhris when we tried the new wines. As I listened to JCB rave about the global potential of Indian wine, it was hard not to think back to that dinner in Bangalore when Mr Grover unveiled his first bottling of La Reserve. Way back then, he believed that India could make good wine.

Now, others share his conviction.