For Throwback Thursday, we rummage through the drawers of culinary history to rediscover how we came to eat the way we do. This week’s throwback finds us aboard an early railway carriage — hungry, hopeful, and about to learn why Victorian travellers coined the term “indigestion house”.

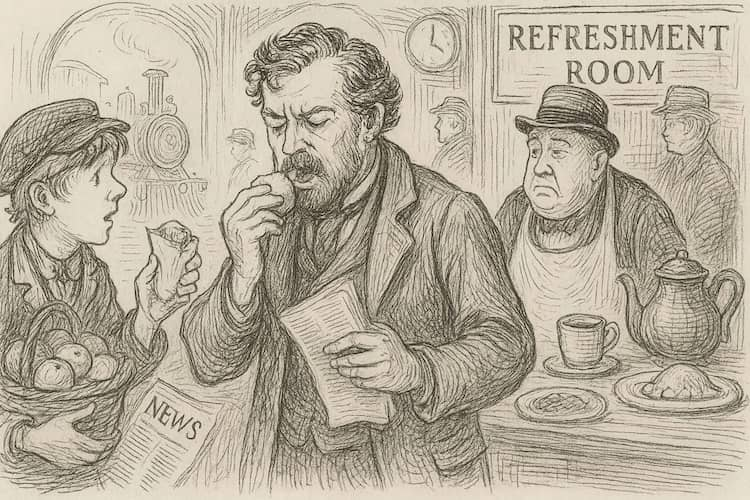

IN THE DECADES before the dining car arrived, eating while travelling by train was closer to a contact sport than a meal. A passenger’s best hope was the packed lunch: jerky, dried fruit, a hunk of bread wrapped in newspaper. Their worst was the dreaded station “refreshment room” — a place so consistently grim that British and American newspapers of the 1850s described them as “indigestion houses,” a euphemism unable to mask the reality of rancid meat pies, sour coffee and the constant threat of missing one’s train while still chewing a cold bean.

The railways, of course, were expanding far faster than their culinary offerings. The world’s first dining experiences were not born out of luxury but logistical necessity. In the mid-19th century, locomotives needed frequent stops for water and wood, leaving passengers a frantic 20-minute window to bolt down whatever the local roadhouse was peddling. Many travellers opted instead for the news butcher — usually a young boy selling stale apples, wilting candy and the occasional questionable sandwich. Scams abounded: meals served just moments before departure, ensuring a customer paid but barely swallowed a bite. The leftovers? Quietly cycled back into service for the next incoming train.

Yet rail travel was transforming societies — shortening distances, shrinking geographies — and eventually, it had to confront the question of how to feed its passengers with something resembling dignity.

The Birth of the Dining Car

If the early railway meal was a gamble, the dining car was its antidote. The breakthrough came in 1867 in the United States, when George Pullman introduced the “hotel car” — a sleeper fitted with a compact kitchen. A year later, the Delmonico, the world’s first dedicated dining car, rolled out onto American tracks, draped in velvet curtains, white linens and ambitions far loftier than a ham sandwich.

Competition quickly pushed railways to turn cuisine into a marketing tool. Dining cars became “loss leaders” — rail operators knowingly spent more on meals than they earned, banking instead on the rising prestige of their trains. By the 1880s and 1890s, a passenger might find themselves at a polished mahogany table, eating saltwater oysters on a westbound journey and freshwater fish on the return, their waiter gliding through a moving carriage with the poise of a ballroom dancer. The invention of the vestibule — a flexible, covered gangway between carriages — finally allowed passengers to reach the dining car without risking a tumble onto the tracks.

Menus became regional showcases. The Northern Pacific Railway boasted potatoes weighing up to two kilos, cooked evenly by stabbing them with ice picks; the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul offered Christmas feasts of antelope steak, stuffed suckling pig and pheasant in aspic. In cramped kitchens where temperatures hit 51°C, chefs turned out multi-course meals using ingredients picked up along the route. One such innovation — a pre-mixed blend of lard and flour used on Southern Pacific trains — would later inspire what became known as Bisquick.

Across the Atlantic, British dining cars arrived in 1879 with a six-course menu written ceremoniously in French. Opulence, it seemed, travelled well.

India’s Railway Table: Caste, Curry, Chai

While the West perfected the rolling restaurant, India’s railway story began differently. When the first train steamed out of Bombay in 1853, no food was offered at all. Instead, stations hosted tightly segregated refreshment rooms: Europeans in one, Muslims in another, and Hindus often further divided by caste. The railways were revolutionary, but the table remained profoundly stratified.

Still, the trains produced their own culinary innovations. The most famous is the Railway Mutton Curry, born on the Frontier Mail. British officers found the traditional Bengali mangsho jhol too fiery; pantry cooks responded with a milder version thickened with yoghurt and coconut milk — a golden curry that has outlived the empire that inspired it. The Railway Cutlet, an Anglo-Indian adaptation of a French côtelette, became another enduring classic: breaded, fried, and tailored to suit everything from mutton to chicken.

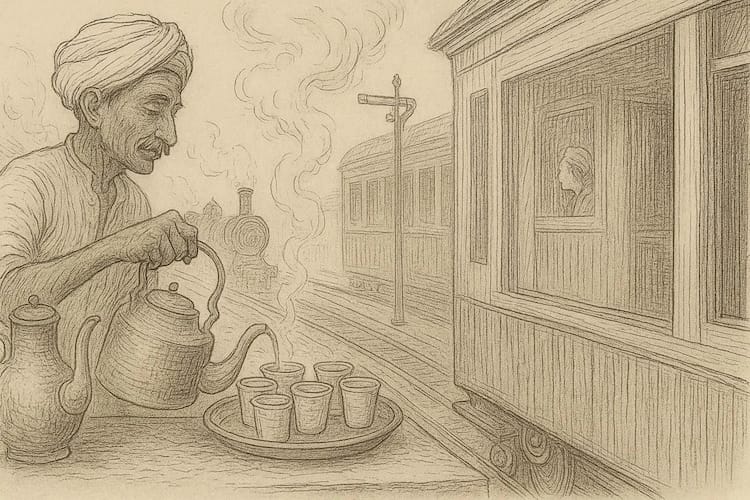

Perhaps the most profound legacy, however, is chai. India’s tea habit owes much to the railway network, which the Tea Board used to popularise the drink in the early 20th century. Vendors brewed milky, sugary tea to match local tastes for lassi, and in doing so cemented chai as a national ritual — the steam, the whistle, and the cup becoming inseparable in the Indian imagination.

Parallel to all this flourished the tiffin culture. Wealthier passengers dined in restaurant cars; others brought elaborate home-packed meals — puri, dry aloo sabzi, laddoos — carried in brass tiered boxes. Even today, the sight of a family unpacking a fragrant tiffin on a train is a lingering echo of this older era.

The Golden Age and the Slow Fade

By the 1930s, the dining car reached its zenith. Air-conditioning cooled the once-sweltering galleys, menus rivalled those of five-star hotels, and newspapers romanticised the idea of “dinner in the diner” as the height of civilised travel. It was a short-lived splendour.

War rationing in the 1940s stripped menus bare. The economics worsened: for every dollar earned on dining, American railways were spending $1.38. By the post-war decades, fresh cooking gave way to reheated trays, vending machines, trolley carts and, eventually, the standardised microwave meal.

Yet the nostalgia endures. Luxury tourist trains still offer white-gloved service; railway cutlets still appear on breakfast menus; chai still arrives in earthen cups. The dream of a meal served at speed, scenery blurring past the window, remains an almost mythic part of railway lore.

A Legacy on the Move

What railway dining ultimately illustrates is how travel reshapes appetite — how necessity sparks innovation, how class and caste mould the menu, how chefs can conjure elegance from a 2×6-metre sweatbox rattling across a continent. It is a story of human ingenuity under pressure, of comfort chased at high speed, of nations learning to feed themselves on the move.

And on this Throwback Thursday, it reminds us that the dining car was not just a place to eat, but a fleeting theatre of modernity — a small, swaying room where the world learned to cook while in motion.