EGGNOG is a strange thing to love. It’s thick but drinkable, alcoholic yet infantilised, indulgent but medicinal in origin. It arrives every December with the authority of tradition, then disappears just as abruptly, leaving behind vague memories of nutmeg, dairy, and regret. Few seasonal foods inspire such divided loyalty. And yet, eggnog persists — a stubborn, creamy relic that refuses to be modernised out of existence.

To understand eggnog is to understand how Christmas eating works at large: through excess, preservation, performance, and selective forgetting.

FROM MEDIEVAL POSSET TO COLONIAL STATUS SYMBOL

Eggnog’s roots lie not in holiday cheer but in medieval sustenance. Its earliest ancestor was posset, a hot drink made of milk curdled with ale or wine, thickened with eggs and sweetened with honey or sugar. Posset was less treat than tonic — prescribed for colds, sleeplessness, and general malaise. In 14th- and 15th-century England, it was commonly served to the sick, the elderly, and those recovering from long journeys.

What distinguished posset — and later eggnog — was its ingredients. Milk, eggs, and spices were expensive. So was alcohol. This was not peasant fare; it was the drink of landowners and clergy, served in elaborately decorated bowls and sipped ceremoniously. Nutmeg, now a supermarket staple, was once a luxury spice imported through complex colonial trade routes. A sprinkle of it signalled wealth as clearly as silverware.

The name “eggnog” itself likely reflects this lineage. “Nog” may derive from noggin, a small wooden cup, or from nog, a strong ale brewed in East Anglia. Either way, the word suggests heft, potency, and purpose.

When British colonists carried posset across the Atlantic, the drink changed. In North America, milk and eggs were abundant. Rum, imported cheaply from the Caribbean, replaced brandy or wine. Eggnog shed its medicinal seriousness and became a celebratory indulgence — still rich, still spiced, but no longer confined to sickbeds.

EGGNOG & THE ARCHITECTURE OF EXCESS

Eggnog’s transformation coincided with a broader shift in Christmas itself. The modern idea of Christmas as a season of abundance — heavy food, rich drink, suspended restraint — is largely a 19th-century invention. As historian Stephen Nissenbaum has argued, Christmas became a domestic, sentimental festival during the Victorian era, shaped by literature, urbanisation, and the rise of the middle class.

Eggnog fit perfectly into this architecture of excess. It was caloric, communal, and performative. Recipes scaled easily for crowds. Bowls could be ladled repeatedly. Alcohol softened the conversation. In the United States, eggnog became a staple of Christmas parties, church gatherings, and family reunions.

But it also retained its liminal identity. Unlike cake or pudding, eggnog is neither food nor drink in the conventional sense. It occupies a strange middle ground — thick enough to coat the mouth, light enough to sip. That ambiguity is part of its appeal and its discomfort. Eggnog doesn’t refresh; it envelops.

A DRINK WITH A REPUTATION

Eggnog’s reputation has never been entirely wholesome. Even in its early American incarnations, it was known for its strength. George Washington reportedly served an eggnog containing rum, brandy, rye whiskey, and sherry at Mount Vernon — a recipe so potent it omitted instructions altogether, presumably assuming the drinker’s fortitude.

This potency gave eggnog a slightly unruly edge. It was associated with loosened morals, extended celebrations, and — occasionally — chaos. The most famous example is the Eggnog Riot of 1826 at the United States Military Academy at West Point, where cadets smuggled whiskey into the barracks to fortify their eggnog, resulting in vandalism, injuries, and court-martials.

That incident cemented eggnog’s dual identity: cosy and dangerous, nostalgic and volatile. A drink that appears benign, even childish, but carries adult consequences.

INDUSTRIALISATION & THE LOSS OF RITUAL

For much of its history, eggnog was made fresh — whisked laboriously by hand, tempered carefully to avoid curdling, spiked to taste. The act of making it was part of its meaning. Like plum pudding or fruitcake, eggnog demanded time, attention, and a tolerance for mess.

The 20th century changed that. Advances in refrigeration, pasteurisation, and mass production turned eggnog into a seasonal commodity. Supermarkets began selling it pre-mixed, shelf-stable, and aggressively branded. Alcohol was removed or sold separately. Nutmeg became optional. Texture was standardised.

What was gained was convenience. What was lost was ceremony.

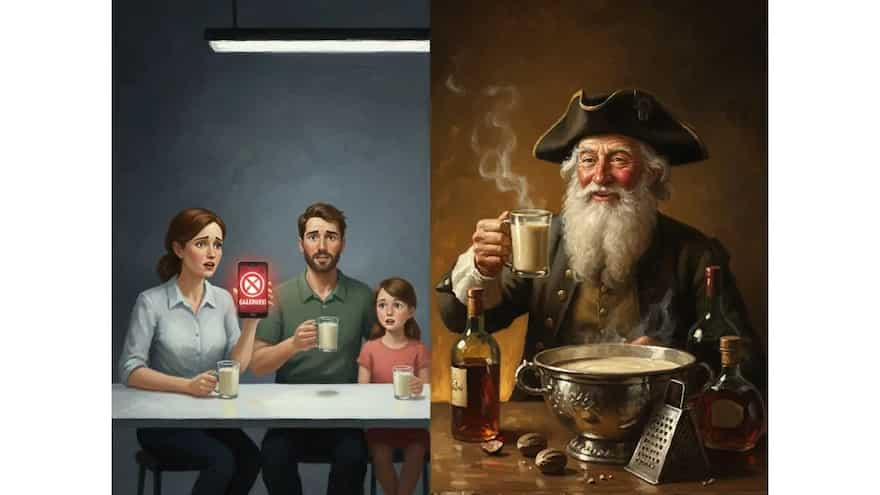

This shift mirrors a broader transformation in festive food culture. As Christmas became more commercialised, labour-intensive dishes were replaced by shortcuts. Eggnog, once a drink you made, became something you bought. Its presence became symbolic rather than participatory.

And yet, the homemade version never disappeared entirely. Families continued to argue about raw eggs, alcohol ratios, and whether whipped cream belonged on top. Eggnog remained a site of debate — a marker of authenticity, risk tolerance, and tradition.

FEAR, SAFETY, & THE MODERN PALATE

Eggnog’s decline in popularity over the past few decades is often attributed to changing tastes. It’s too rich, too sweet, too old-fashioned. But underlying these aesthetic objections is something more modern: fear.

Raw eggs make people nervous. Dairy feels heavy. Alcohol in creamy form seems excessive. Contemporary food culture prizes lightness, transparency, and health signalling. Eggnog offers none of these things. It is opaque, indulgent, and unapologetically caloric.

Ironically, traditional eggnog recipes relied on alcohol not just for flavour but for safety. Studies have shown that sufficiently alcoholic eggnog can neutralise harmful bacteria over time — a fact that would have been understood instinctively long before it was proven scientifically.

Eggnog wasn’t reckless. It was pragmatic.

WHY EGGNOG ENDURES

Despite its contradictions, eggnog persists because it fulfils a specific emotional role. It is not a drink you reach for casually. It is a drink that marks time. Its very awkwardness makes it seasonal. You wouldn’t want it year-round — which is precisely why it belongs to December.

Eggnog asks us to slow down, to accept heaviness, to indulge without justification. It resists optimisation. It doesn’t travel well. It doesn’t photograph easily. It cannot be easily rebranded as wellness.

In a season increasingly dominated by efficiency and consumption, eggnog remains stubbornly ceremonial. You pour it knowing you won’t finish the carton. You grate nutmeg knowing it’s excessive. You drink it because it’s December — and because December permits a certain kind of nonsense.

Eggnog survives not because it adapts, but because it refuses to. It is a reminder that some traditions persist not through logic or popularity, but through ritual, memory, and the quiet pleasure of doing something simply because we always have.